This guide will help you understand all about psyche splitting off from trauma and how to heal from childhood trauma splitting.

A traumatic event, especially childhood trauma can leave the individual with an entrenched self-alienation or intense self-hatred.

Although they might be able to go on with their life, they suffer from internal struggles inside their mind and body.

Adaptation to trauma requires a splitting of self and identity, which can create an inner war.

To heal from a traumatic childhood and other types of trauma, the individual needs to see his different parts as separate from his Self and to “befriend” them in a compassionate way.

Whereas the idea of being “nice,” “taking care of” or being “compassionate” to themselves was met with disgust and avoidance, once the individual comes to love their hurt, lost, and lonely parts, their self-disparagement, self-hatred, and disconnection can turn into self-compassion as they begin to develop internal attachment relationships to these young selves.

- What Is Trauma Splitting?

- Psyche Splitting Off From Trauma: 8 Signs of Childhood Trauma Splitting

- How Childhood Trauma Can Cause Splitting?

- The “False Self”: The Price of Self-Alienation

- How to Heal From Childhood Trauma Splitting and Heal Your Fragmented Self?

- Best 10 Proven Ways to Heal From Childhood Trauma Splitting

- Pro Tip. Work With a Therapist

- Conclusion

What Is Trauma Splitting?

Childhood Trauma Splitting is a trauma response that allows an individual to tolerate overwhelming emotions.

Trauma Splitting, Structural Dissociation, or fragmentation is when the Self splits into different parts, each with a different personality, feelings, and behavior.

This can create an internal conflict (e.g., between vulnerability and control, closeness and distance). (*)

Psyche Splitting Off From Trauma: 8 Signs of Childhood Trauma Splitting

Survivors of abuse, neglect, and other traumatic experiences might appear superficially an integrated whole person but would also manifest signs of trauma splitting.

The following are some of these signs:

1. Experiencing intense conflicts between trauma-related perceptions and impulses (e.g. “the worst is going to happen,”) versus here-and-now assessments of danger (e.g. “I know I’m safe here.”)

2. Experiencing paradoxical symptoms, such as the desire to be kind and compassionate toward others, on one hand, and intense rage or even impulses to violence, on the other.

3. Somatic symptoms, such as unusual pain sensitivity or uncharacteristically high pain tolerance, eye blinking or drooping, stress-related headaches, etc.

4. “Regressive” behavior, such as body language that seems more typical of a young child than an adult of their chronological age (appearing shy, fearful, unable to tolerate being seen, or unable to make eye contact).

5. “Regressive” thinking, such as black/white thinking, words or style of expression more typical of a child than an adult (using shorter sentences, expressing themes related to separation and caring), feeling empathically failed when not well understood.

6. Patterns of indecision or self-sabotage that manifest in frequent changes of job, career, or relationship, and a history of success in life alternating with self-sabotage (e.g. hard work being suddenly undone by self-destructive actions) or inexplicable failure, and difficulties in daily life choices such as an inability to choose what to wear in the morning, what to eat for lunch, etc.

7. Memory symptoms that manifest in memory gaps and “time loss” (e.g. difficulty remembering how time was spent in a day, difficulty remembering conversations, getting lost while driving somewhere familiar, forgetting well-learned skills, engaging in behavior one does not recall, etc)

8. Patterns of self-destructive and addictive behavior activated by fight and flight-driven parts.

* Parts driven by the fight response might engage in high-risk behavior or attempt to harm the body in an attempt to get relief from the implicit memories.

* Flight parts tend to engage in eating disorders that result in numbing or addictive behavior that alters consciousness, which allows distance from unbearable emotions and flashbacks.

Related: Stop Self-Sabotage: How to Tame Your Inner Teenager and Heal Your Inner Child?

How Childhood Trauma Can Cause Splitting?

The vertebrate cerebrum (brain) is formed by two specialized cerebral hemispheres (left and right).

Under conditions of threat, the brain capitalizes on its left hemisphere to remain positive, task-oriented, and logical under stress.

The disconnected left brain side of the Self stays focused on the tasks of daily living, while the right brain side of the Self remains in survival mode, ready to run, frozen in fear, praying for rescue, or too ashamed to do anything but submit.

Moreover, the corpus callosum, (the part of the brain that makes possible communication between the right brain and the left brain) develops slowly and only becomes fully developed around the age of twelve

Thus, in the early years of childhood, the experience of the right brain and the left brain is relatively independent, which facilitates splitting should the need arise.

The left hemisphere has a tendency to grasp the gist of a situation, which affects accuracy but makes it easier to process new information.

The right hemisphere, on the other hand, is totally truthful and only identifies the original information. It does not “forget” the nonverbal aspects of experience and does not interpret it.

The left hemisphere uses language to describe experience and information, whereas the right hemisphere is more visual. It can recognize differences and similarities between stimuli but lacks words to describe them.

So emotions, while experienced on both sides of the brain, can only be verbalized by the left hemisphere. The right hemisphere might act on the emotion but can’t describe it in words.

So without an exchange of information, the left hemisphere might have no memory of the right hemisphere’s emotion-driven actions or reactions.

The left-brain, present-oriented self tends to avoid the intrusive right-brain, survival-oriented parts or judge them as bad qualities to be modified and tries to carry on desperately trying to be “normal”.

Related: Unhealed Childhood Trauma In Adults: 9 Therapy Approaches to Deal With Childhood Trauma

The “False Self”: The Price of Self-Alienation

The act of compartmentalization allows trauma survivors to function well in their lives. However, they usually report suffering from feelings of fraudulence or “pretending.”

Without realizing that each side of the personality is equally “real”, they misinterpret the intense feeling memories of the “disowned” child part as more “real” than the experience of the “going on with normal life self.”

They don’t realize that these contradictions and intense feelings and distorted perceptions are evidence of fragmentation not proof of fraudulence or internal defectiveness hidden by the ability to function.

The self-alienation is later maintained through self-loathing, disconnection from emotion, addictive or self-destructive behavior, internal struggles between vulnerability and control, closeness and distance (e.g. anxious clinging and pushing others away), love and hate, shame and pride (e.g. yearning to be seen and yearning to be invisible).

Over time, this causes symptoms of anxiety, chronic depression, low self-esteem, and even diagnoses such as PTSD, bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, eating disorders, and even dissociative disorders.

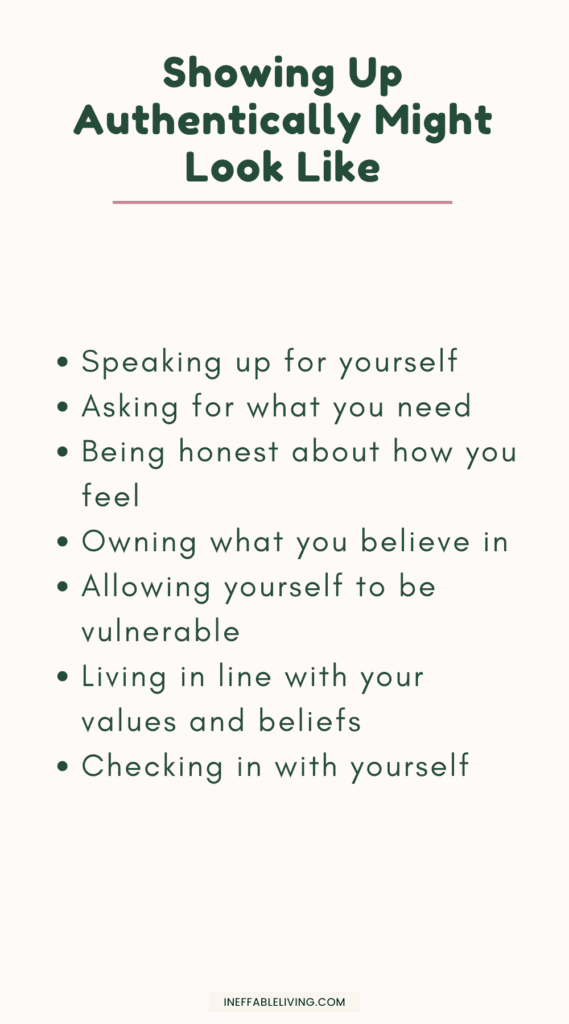

Healing your trauma cannot truly be achieved without reclaiming the lost, disowned parts of ourselves, welcoming them “home,” creating safety for them, and making them feel needed, and valued.

How to Heal From Childhood Trauma Splitting and Heal Your Fragmented Self?

Helping Yourself and Your Parts “Be Here” Now

When trauma-related parts express emergency and survival responses, it’s hard for you to feel safe and present.

The best way to challenge your subjective perception that your symptoms are indicative of current danger or proof of your defectiveness is to bring your attention to these reactions and notice that they represent communications from parts.

By becoming mindful and curious instead of reactive, you develop new responses to triggers and build the capacity to self-regulate and to “be here now,” knowing you are safe.

Only after a period of symptom stabilization, that the traumatic memories can be addressed, in such a way that the autonomic nervous system doesn’t experience dysregulation.

Feeling Safe

Before doing any work on trauma-related issues, you want to make sure that you feel safe enough.

If you are a victim of domestic violence in any form (verbal, physical, sexual, or emotional), I encourage you to get professional assistance to help make you safe.

How safe is your environment? If you are not safe in your environment, what can you do about it?

Best 10 Proven Ways to Heal From Childhood Trauma Splitting

#1. Practice Mindfulness and Increase Self-Awareness

The key to trauma treatment is differentiating between being triggered and being threatened.

It’s only when we know we are safe now that we can effectively process how unsafe it was then.

For individuals with chronic, multi-layered trauma histories and severe dissociative symptoms, getting in touch with their feelings can be overwhelming and evoke anxiety, depression, or impulsive behavior.

Working with symptoms as manifestations of parts allows you to mindfully “notice” your experience rather than “get in touch with it.”

By becoming curious and noticing, you achieve a “dual awareness” – an ability to stay connected to the emotional and somatic experience while also observing it from a mindful distance, rather than lead to retraumatization.

In other words, one part can be overwhelmed by emotional pain, while other parts of the mind and body can be calm, curious, or even empathic, offering support, validation, or comfort.

Read More: 4 Steps to Practice Mindfulness Safely and Support PTSD Recovery

Practical Exercise 1 – Cultivating Mindful Awareness Of The “Here And Now”

The following practice will help you mindfully bring your awareness to the present moment:

* Find a safe place and sit in a comfortable position.

* Allow yourself to collapse. Allow your shoulders to go forward and your gaze downward.

* Take your time, and notice how you feel in your body. Notice what emotions or thoughts arise.

* Then, slowly, lengthen your spine back up. Lift your torso and your head until you are sitting tall. Lift your gaze to look straight ahead of you. Do you notice any openness or expansion? Notice what emotions or thoughts arise now.

* If you find it hard to stay upright and feel an impulse to collapse again, then repeat these steps a few more times until you feel that staying upright comes easily.

Practical Exercise 2 – Get Your Prefrontal Cortex Working

To stop the flooding of feeling memories and help your nervous system, you need to get your frontal lobes working by thinking.

Identify the resources you have that require you to think, such as your job, solving a problem, etc.

Practical Exercise 3 – Notice Your Body Memories

When you find yourself starting to feel overwhelmed, pause for a moment and remind yourself ‘I’m just triggered—these are body memories’

Remind yourself it’s just your body being triggered, and become curious and notice what’s happening rather than panicking.

#2. Acknowledge the Past Without Exploring It

Acknowledging the trauma is completely safe when you allude to the “bad things that happened,” or, “unsafe world you grew up in,” or “the years when nowhere was safe,” in a more general way without vivifying the details of them or using triggering language, such as “rape,” “kidnapping,” etc.

In fact, it is the details of memory and chronological retelling that activates associated memories, dysregulates the nervous system, and can cause re-traumatization.

With the help of a therapist, you can focus on the experience of horror, on the victimization and objectification, or how you survived and adapted to a traumatogenic environment (e.g. hypervigilant anticipation of danger, constriction of activities to what was safe, pleasing people, and gaining their loyalty).

#3. Raise Your Awareness Perspective

When you observe your environment through the lenses specific to each part, you risk creating a distorted perspective.

The fight part is hypervigilant and is not scanning for safety cues

The attachment part only sees the warm smile and the reassuring words, not the danger signals.

The submit part is hypersensitive to data that confirm beliefs in unworthiness and doesn’t see the respect and approval of colleagues, or family members.

Mindful “interest,” rather than “attachment or aversion,” helps you identify the lens through which you are looking.

As a result, you make sure you don’t become flooded with overwhelming emotions and become able to separate from the intense reactions of a part.

Acknowledge the feelings as “the child part’s distress,” and using the quality of curiosity, bear witness to his or her painful experience, rather than identifying with it as “yours.”

Practical Exercise 4 – Unblending

When your traumatized parts are triggered, their feelings flood the body and make you act or react in ways that are not “you” – this is called “blending.”

“Unblending” requires a mindful separation from the intense reactions of the parts through the following steps:

1. Recognize that the overwhelming feelings and thoughts are a communication from parts. If you are not sure it is true, make it an assumption.

2. Describe the feelings and thoughts as “theirs,” such as saying “They are sad— they are overwhelmed.” Notice what happens when you refer to these feelings and thoughts as “theirs.”

3. Create more separation from these parts by changing your position or sitting back. Keep repeating “They are feeling …”

4. Use your wise mind (your compassionate self) to reassure the upset parts. Imagine if these parts were a friend of yours how would you respond? What would you tell them?

5. Get their feedback: Is what you are doing helping? What do they need to feel a little less overwhelmed?

Keep in mind that the key to the success of this technique is repetition.

#4. Feel Empathy For The Child Part

Become curious about your child part that is afraid, ashamed, or hurt, and ask yourself the following questions:

“How old is he or she?”

“Can I see the part?”

“What does he or she look like?”

“What expression is there on that little face?”

Becoming curious about the child part helps you acknowledge the enormity of what this child part has experienced, but also evokes empathy and compassion, as you “see” the child as a helpless, innocent victim.

Make sure you don’t ask the child part “What happened to you at this age?”, instead ask him/her “What kinds of things has this child experienced?” as to not trigger implicit reliving.

Related: How Do We Develop Empathy For Others? The 6 Habits of Highly Empathetic People

Practical Exercise 5 – Facilitating Empathy

If you find it hard to imagine the part you’re struggling with, focusing on a visual representation will help increase curiosity and activate the medial prefrontal cortex:

* Draw a picture of that part and look at the picture with curiosity (What does the drawing tell you about this part? How do you feel toward this part now? What are you learning from the drawing that challenges what you have previously believed about the part?)

Or

* Create a “flow chart” that tracks the internal relationships between the parts in conflict. Start with an initial trigger and then note which parts were activated.

Then draw a representation of the compassionate normal life self taking the activated parts “under her wing,” or “into her arms.”

Related: 12 Actionable Tips to Fix Lack of Empathy and Become a Strong Empath

#5. “Help” The Child Parts That Are So Frightened

For example, a person who had been kidnapped as a child and who is still afraid of leaving the house even as an adult can access her child part by doing the following:

1. Identifying the part “who is afraid to leave the house”.

2. Asking her if she’d be willing to show a picture that would help you understand what she’s afraid will happen if you walk out of the door.

In this case, being kidnapped.

3. Asking her, “Did you think it could happen again?”

“Did you know that can’t happen at my house?”

“Do you know why? Because I’m too big now, and no one can see you because you’re inside me.”

By identifying the wounded child part and the root of their fear that continued to affect your life and distort your reality, and becoming able to correctly interpret “your” fear as a communication from a frightened little child, you can more easily work on your fears and demonstrate to the part that the danger isn’t there anymore.

In the example above, one way to work through the fear of going out is to visualize the door the little child was afraid of and praise her for knowing that she shouldn’t open the door.

Then, lovingly visualize taking hold of the child, somatically communicating that she was there and would not let anyone harm her until the child part becomes able to trust that the door she is opening is not the same door that had once led to a dangerous world.

#6. Befriend Your Parts

For many trauma survivors, the ability to be compassionate or comforting to others doesn’t come so easily when it comes to offering themselves the same kindness

“Befriending” your parts helps you develop the practice of self-acceptance, one part at a time.

This self-acceptance will help you feel safe in any relationship and give you the emotional resilience you need to tolerate hurt, loneliness, disappointment, frustration, and rejection—risks that are inherent in any close relationship.

In that sense compassion for the child who lived through these traumatic events can be more important than knowing the details of what happened.

Practical Exercise 6 – Mindfully Connect With Your Child Part’s Pain

Mindfulness is key to helping you befriend your child parts, not only because of its regulating effect on the nervous system but because it also facilitates the capacity for “dual awareness” allowing intense emotions can be held and tolerated while you explore the past.

* Identify your child’s part and try to connect to a felt sense of the child self’s painful emotion.

* Simultaneously, feel the length and stability of your spine, the in and out of your breath, the beating of your heart, and the ground under your feet.

#7. Dealing with Suicidal, Self-Destructive, Eating Disordered, and Addicted Parts

Understanding High-Risk Behavior

Self-harm, suicidality, eating disorders, and substance abuse are relief-seeking behaviors rather than destruction-seeking ones.

In fact, the reason behind self-harm is the pursuit of mastery over unbearable feelings or relief-seeking from physical and emotional pain, which is the only way the person knows how to have no better way of self-soothing.

In fact, childhood trauma survivors have been deprived of the normal experiences of tension relief (i.e., the soothing of a secure attachment relationship with the parent who offers reassurance and comfort). At the same time, the abuse has turned the body into a vehicle for releasing tension.

The child learns to avoid connection and to rely almost exclusively on their own resources since they cannot trust or depend on others for soothing.

These resources might include drugs, alcohol, self-starvation or binging and purging, and self-injurious behaviors, such as cutting, scratching, burning, hitting, etc.

How Self-Destructive Behaviors “Work”

The most challenging thing about treating self-destructive behavior is how effective it is in producing relief it can be.

Harming the body has the same effects as any injury or threat:

* It stimulates adrenaline production, which increases energy, focus, feelings of power and control and decreases emotional and body sensation.

* It increases endorphin release, which facilitates a relaxation/pain-relieving effect.

These responses occur quickly in a way that almost provides instant relief from the intrusive, overwhelming emotions and sensations.

That is until the individual begins to develop tolerance and needs to increase the harming in severity or frequency in order to induce the same relieving effect.

Over time, as the individual develops more tolerance, the self-harming behavior often spirals out of control.

Practical Exercise 7 – Dealing With High-Risk Behavior

Rather than acting on suicidal ideation, active addiction, or self-harm, attend to the internal struggle by asking yourself the following question:

* Which “I” wants to self-harm? The depressed part?

* What triggered this impulse?

* What problem might this be a solution for?

* What is it that I’m hoping for as a result of the action?

* How else can I tolerate the pain?

Each of these answers requires a different solution – one that you can only provide after gaining an understanding of the parts.

In addition, you can ask yourself

* Where is the normal life part? Why is he or she missing in action?

* Is the normal life self temporarily disempowered by the intense emotions and impulses of the distressed parts?

* What could the normal life self do to understand and soothe distressed parts?

#8. Build Compassion

Two strategies can help you build compassion: forgiveness and gratitude.

1. Forgiveness

Forgiveness is the act of letting go of your own negative feelings, whether or not the other person deserves it.

Resentments can weigh heavy on our mental and physical health.

Chronic anger keeps you stuck in fight or flight and increases your risk for heart disease.

In fact, research from The John Hopkins Hospital found that forgiveness practices lower the risk of heart attack, improve sleep, reduce pain, and decrease reported symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Forgiveness shouldn’t be a forced process – It is a choice.

The best way to learn how to forgive is to reflect on your harmful actions and the ways you’ve hurt others. Once you learn how to forgive yourself, you can forgive others.

As you reflect on others’ harmful actions, you might discover that people hurt others because they hurt themselves – you arrive at an understanding that no one is perfect.

Practical Exercise 8 – Forgiving

Write a letter about something you’re struggling to forgive and let go of. This letter can be to yourself or to another person.

Take a moment to reflect on the hurt. What emotions are you aware of? What thoughts come to your mind?

If you feel ready to free yourself from grudges, express your forgiveness and the reasons behind your decision.

If the letter is written to another person, you can either choose to mail the letter or throw it away. Either way, this practice is for you and your therapeutic use.

2. Gratitude

You might not be able to exempt yourself from difficult life experiences or painful emotions, but you can always take a moment to express gratitude.

It is hard to feel grateful and stressed at the same time. Therefore, focusing your mind on gratitude can help get you out of your stress response and build positive emotions

It has been shown that having a regular gratitude practice strengthens the immune system and lowers blood pressure.

Practical Exercise 9 – Expressing Gratitude

Find a quiet place where you can sit and reflect.

Bring to mind an intention to focus the next several minutes on gratitude for yourself, people, and things in your life.

Gratitude for yourself

Take a few deep breaths and thank yourself for making time and space for this practice.

Extend this positive feeling by appreciating other aspects of you – your smile, an act of kindness you offered to someone.

Gratitude for someone else in your life

Turn your attention to a person or people who have been kind to you – a neighbor who helped you, a family member who supported you, or even a stranger who offered you an act of kindness.

Take a deep breath as you give thanks to this person.

Gratitude for your surroundings

Bring your attention to one thing you appreciate in your surroundings – the home in which you live, the shade of a tree, the beauty of a sunset, etc.

Take a deep breath as you give thanks for these things.

Make it a habit to write down every day at least three things you feel grateful for.

You can take a “savoring walk,” in which you walk outside while observing and expressing gratitude for the sights, sounds, and smells you experience.

Read More: Daily Gratitude Ideas: 10 Ways to Practice Gratitude Every Day

#9. Self-Care

When to take a step back from doing these exercises?

If you begin to feel overwhelmed, take a break and do something else. The following are some signs to help you recognize when you’re feeling overwhelmed:

- You begin to lose your sense of time or feel that you are not aware of your surroundings (symptoms of dissociation)

- You experience flashbacks, or have more frequent or more intense flashbacks related to the traumatic events

- You experience feelings that seem to be out of control

- You engage in compulsive behaviors and addictions

- You begin to develop eating disorder (you stop eating, you binge, or you binge and make yourself throw up)

- You begin to isolate yourself and avoid other people

While you are on a break practice self-care:

Physical Self-Care

- Eat regular meals that are healthy and balanced

- Exercise

- Get a massage

- Play sports

- Take a warm bath or shower

- Do housework or yard work

Psychological Self-Care

- Journal

- Meditate

- Listen to soothing audio recordings

- Read your favorite book

- Say no to others’ requests

Emotional Self-Care

- Spend time with family members you love

- Watch your favorite movies or tv shows

- Listen to your favorite music

- Laugh or cry

Spiritual Self-Care

- Spend time in nature

- Go to or join a church or other spiritual group

- Read a spiritually oriented book

- Practice gratitude and appreciation

- Do something to help better the world

#10. Resources In Review

When you are feeling anxious or depressed, remind yourself to take positive actions to soothe yourself by creating a list of resources.

An example of resources might include the following:

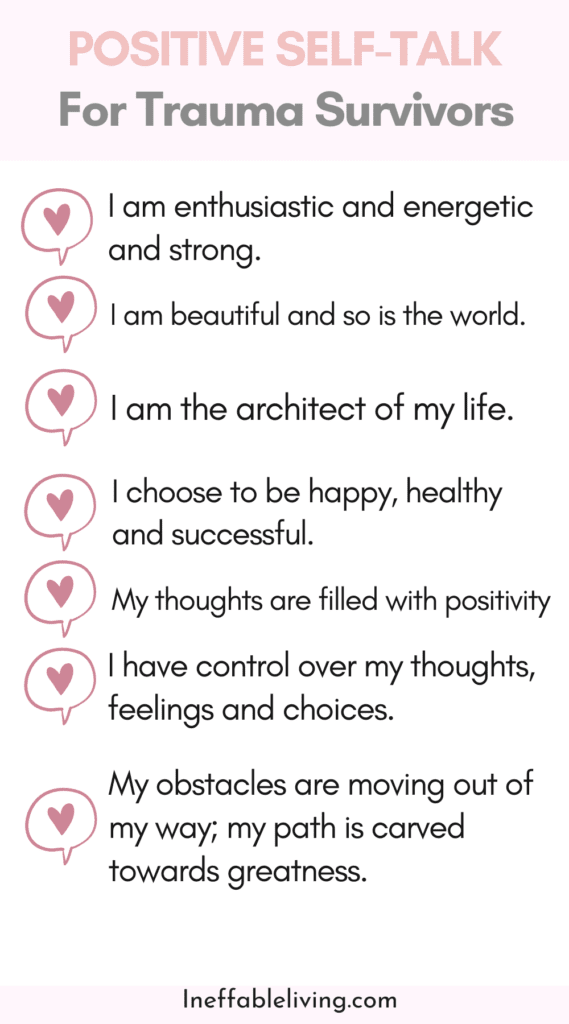

* Replace negative self-statements with positive beliefs.

* Challenge thinking distortions with disputing questions (What evidence do I have that what I believe is actually true?)

* Consciously breathe with a 4-count inhale and 4-count exhale.

* Mindfully scan your body, noticing sensations with curiosity and self-acceptance.

* Give yourself positive messages about your emotions (e.g., “I can allow my feelings to come and go like waves in the ocean”).

* Replace “I am sad” with “I feel sad.”

* Visualize a safe or peaceful place.

* Ground yourself by feeling your feet on the earth and releasing your weight into gravity.

* Practice vagus nerve stimulation (e.g., humming, Valsalva maneuver, diving reflex).

* Write a forgiveness letter to yourself or another person.

* Journal about gratitude.

* Engage in a creative activity (paint, make music, dance, write a poem).

* Practice mindfulness through meditation or yoga.

Place a copy in your wallet or near your desk.

Pro Tip. Work With a Therapist

There is a lot that you can do to support your healing journey.

But healing your inner child alone can be an overwhelming thing to do on your own, especially when the emotional turmoil has been repressed for a long time.

Consider working with a therapist to support you on your healing journey.

To find a mental health care provider near you, call 1-800-662-HELP (4357) or you can use online therapy.

Conclusion

Adaptation to severe trauma, especially during childhood, requires the splitting of the self, which can create an inner war that makes it almost impossible to reprocess your trauma without re-traumatizing yourself.

When you take a mental step back, increase curiosity about the younger parts that are traumatized, notice the bodily and emotional signs that communicate “their” feelings, and then experiment with what might help the parts feel safer, you will be “processing” post-traumatic memory.

Resources

- Portions of this article were adapted from the book Healing the Fragmented Selves of Trauma Survivors, © 2016 by Janina Fisher. All rights reserved.

- Splitting as a consequence of severe abuse in childhood – PubMed (nih.gov)

- Splitting | DID-Research.org

- (PDF) When Trauma Strikes the Soul: Shame, Splitting, and Psychic Pain (researchgate.net)

- The Effects of Childhood Trauma (verywellmind.com)

- Trauma Types | The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (nctsn.org)

- Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) (cdc.gov)

- Study: Experiencing childhood trauma makes body and brain age faster (apa.org)

- “The Biological Effects of Childhood Trauma” – PMC (nih.gov)

- Frontiers | Childhood Trauma and Chronic Illness in Adulthood: Mental Health and Socioeconomic Status as Explanatory Factors and Buffers | Psychology (frontiersin.org)

Comments are closed.